ORTODOXIA CATHOLICA

Orthodox Blog of Father Matei Vulcănescu

Ecumenical Patriarch Maximos V

World War II ended in 1945, and immediately, the United States and the Soviet Union began jockeying for leadership in the postwar world. The Soviets swept as many countries as possible into their orbit; meanwhile, the United States adopted the Truman Doctrine, a foreign policy based on the containment of Communism throughout the world. Orthodoxy became one of the many proxy fronts in the Cold War: as the Soviets attempted to use the Moscow Patriarchate to the other Orthodox Churches to support Communism, the United States backed the Ecumenical Patriarchate as a pro-Western counterweight.

Enthroned in early 1946, the new Ecumenical Patriarch, Maximos V, proved, for several reasons, to be too weak to serve as an effective leader of the Church of Constantinople at this critical moment. Today he’s a mostly-forgotten footnote in history, most notable as the man who preceded the great Athenagoras, the strong, staunchly pro-American Patriarch who succeeded him. Remarkably, the CIA has released a large number of documents under the Freedom of Information Act that help tell the story of Maximos’ patriarchate — a story that, but for these documents, would be largely inaccessible to us. In this article, I use those CIA documents, and a few other contemporary sources, to tell that story. I’m doing this in part because it’s an interesting piece of church history, but also because it shows how closely the CIA was following events in the Orthodox world. These are only the CIA documents that have been declassified under FOIA, and it’s likely that other documents exist that have not been released to the public. Even with that caveat, these sources help us reconstruct a critical episode in modern Orthodoxy.

***

On February 20, 1946, Metropolitan Maximos of Chalcedon was unanimously elected Ecumenical Patriarch Maximos V. He had been the power behind the throne during the decade-long reign of the late Patriarch Benjamin, and at just 48 years old, Maximos appeared to have a long ministry ahead of him as “first among equals” in the Orthodox world.

But, no: he had a rather short ministry ahead of him. Maximos resigned 32 months later, on October 18, 1948.

The first signs of trouble appeared in the fall of 1946. A November 22 CIA report said, “A source in close contact with the Patriarch reports that Maximos is suffering from an acute nervous attack and shows grave symptoms of insanity.” On December 16, according to the CIA, “physicians had informed the Phanar that Patriarch Maximos’ illness required treatment in a sanitarium in Switzerland, and that arrangements were being made for his immediate departure for that country.”

Maximos tried to resign as Patriarch, but the Greek government refused to accept his resignation, because a new Patriarchal election would mean that the Greeks would have to find common ground with the Turks on a candidate.

Sometime before Christmas 1946, the CIA received word that Maximos’ condition remained serious. “Patriarch Maximos is reported to continue to suffer from recurrent attacks of nervous depressions and insomnia, although there are intervals following these attacks during which he is quite normal. Source, who visited Maximos at his summer residence on Heybeliada [Chalki] where he is being attended by his personal physician, stated that Maximos was hopeful of being sufficiently recovered to officiate at the Christmas service at the Phanar, and also to remain at the Phanar until after the first of the year.” (This account appeared in a CIA report dated Jan. 16, 1947.)

Greek media broke the news of the Patriarch’s mental illness on December 29, 1946. The next day, the Phanar denied everything with the statement, “His Holiness is in good health and will not leave for Switzerland.”

On January 3, 1947, the story reached the United States. The Chicago Tribune reported on a special commission of mental health experts that had examined the Patriarch and determined that he was “suffering from a nervous disorder.” The commission reported that Maximos’ “intelligence is normal” and that he would probably recover with treatment. The Tribune went on:

Soon after his election he was reported to have paced across a room in the patriarchate and cried out, “I know now this is no life for a young man.”

Informants said that since then the head of one of the mightiest thrones of religion had suffered from what was described by his associates as “restriction phobia.”

Coupled with this has been the heavy burden of the office, particularly now when the patriarch is confronted with moves by the Russian Orthodox churchmen to expand their orbit of influence.

The Tribune closed by citing sources suggesting that Archbishop Athenagoras, primate of the Greek Archdiocese of North and South America, “might be a candidate.”

On January 16, the CIA reported, “Serious thought is being given to the deposition of the Patriarch, but his followers are reluctant to take such a step until they are satisfied by the doctors that Maximos’ condition is incurable.” Meanwhile, an unrelated scandal emerged — it seems that in 1940, four Greek attorneys engaged by the Patriarchate had stolen money that a wealthy benefactor had bequeathed to the Patriarchate in his will. Although the late Patriarch Benjamin led the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 1940, everyone knew that then-Metropolitan Maximos was the real power behind the throne. The CIA observed, “As Patriarch Maximos was in complete charge of the Patriarchate in 1940 when the late Patriarch Benjamin was ill, certain elements in the Phanar wish Maximos to assume some of the responsibility for this scandal.”

The Soviet government had, of course, taken notice of the situation in Istanbul. From a February 14 CIA report: “The Turkish papers … have published a statement to the effect that the Soviet Consul General had placed the Russian summer Embassy in Buyukders [Büyükdere] at the disposal of the Patriarch. Phanar officials insist, however, that there is no foundation to this report and are of the opinion that the two papers in question obviously wish to create difficulties for the Patriarchate by giving the impression of close collaboration with the Soviets.”

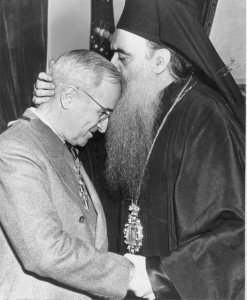

President Truman and Archbishop Athenagoras, February 1947

A few days prior to that CIA report, Archbishop Athenagoras was in Washington, awarding President Truman with a piece of the True Cross. This is when the famous photo was taken of Athenagoras kissing Truman on the head. (It seems likely that this event was arranged a couple weeks in advance, when President Truman held an off-the-record meeting with Athenagoras on January 28.)

On March 12, President Truman addressed Congress and formally articulated, for the first time, what has become known as the Truman Doctrine: “the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” That’s a fairly well-known fact, but what’s often forgotten is that the immediate cause of Truman’s speech was the news that the British would stop providing aid to the Greek government, which was embroiled in a civil war against the Greek Communist Party. The British had also been aiding Turkey, and in his speech, Truman also asked Congress to provide aid to the Turks. Altogether, Truman asked Congress to approve $400 million in aid to the Greek and Turkish governments, and to authorize sending US military personnel and equipment to the region.

On March 20, the CIA reported about the possibility of the Turkish government appointing a medical commission to determine whether Maximos could continue as Patriarch. “At present the Turkish Government wishes to have the Phanar in charge of a powerful man, who could cope with Patriarch Alexei and the religious policies of Russia.” The same CIA report commented that a Moscow Patriarchate delegation, which had been trying to visit Istanbul for nearly a year, had failed to obtain visas from the Turkish authorities and was now visiting Damascus, Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Cairo.

Three days later, another CIA report described internal attempts to remove Maximos, coming from within the Greek community in Turkey. The anti-Maximos faction had been his enemies “since the time when [Maximos] was Metropolitan of Chalcedon.” The Greek government was considering the matter, and the CIA expected the Holy Synod of the Patriarchate to elect a new Patriarch after Pascha.

Meanwhile, on April 8, Patriarch Alexei of Moscow sent official invitations to the heads of the Orthodox Churches to attend a preconciliar conference, which he hoped would set the stage for an “ecumenical council” in Moscow in 1948.

Pascha came and went with no patriarchal election. On May 9, the New York Times reported that Patriarch Maximos was having an “acute nervous breakdown,” and Archbishop Athenagoras was named as the leading candidate to succeed him. The interest of US intelligence officials in the matter did not go unnoticed by the Times: “No official support of Archbishop Athenagoras has been expressed by the Americans although United States military intelligence is watching the race.” The Times added, “The Turks call the Archbishop Turkey’s unofficial ambassador to the United States, so cordial are his relations with the Turkish Government… The Greek Government is favorable to Archbishop Athenagoras but is reluctant to have such an efficient emissary leave the United States and its wealthy contributors to Greek causes.”

Nine days later, on May 18, the Chicago Tribune ran a story saying that Maximos “gives up his throne,” having set sail for Greece. Public speculation was that he would never return to the Phanar.

On May 21, the CIA reported that Maximos was traveling to Athens to consult with specialists. “If he is found to be incurable, it is believed that his resignation as Patriarch will be accepted.” But a bit later, on July 3, the CIA seems to have corrected itself, saying that the real reason for Maximos’ visit to Greece was not the reported health issues but “for consultation concerning three major issues:”

(a) Whether Maximos should resign in favor of a stronger personality;

(b) If he should resign, what candidate would be favorable to Athens; and

(c) How can the Phanar deal with the increasing prestige of Patriarch Alexei of Moscow.

The CIA report explained why the Patriarch would need to go to Athens to discuss these matters: “The Phanar in Istanbul is dominated financially by the Greek Government.”

In the same report, the CIA noted that Archbishop Athenagoras had “recently been made an honorary citizen of the city of Ankara by the Turks. This privilege has not yet been made public.” (Turkish citizenship was a prerequisite for Athenagoras to be elected Ecumenical Patriarch.)

While Maximos was in Greece, the locum tenens of the Ecumenical Patriarchate sent a letter to the heads of the world’s autocephalous churches, declaring that Constantinople would not participate in Moscow’s proposed preconciliar meeting, and that only the Ecumenical Patriarch had the right to convene a council or a preconciliar conference. The leaders of the Churches of Alexandria, Jerusalem, Cyprus, and Greece agreed, and the Greek media excoriated the Moscow Patriarchate as being a mere tool of the Soviet government. Rejected by the Greek hierarchs, Patriarch Alexei changed his approach toward the end of the year, saying that now he only wanted to host “a conference of the supreme hierarchs of the Orthodox churches.”

***

Improbably, I have not found any documentation on the Ecumenical Patriarchate in the CIA files for more than a year, from July 1947 to August 1948. Given how closely the CIA followed Patriarch Maximos and the Ecumenical Patriarchate up to this point, it seems implausible that they didn’t issue any reports over the year. More likely, these reports do exist but for whatever reason have not been declassified.

On January 28, 1948, the journal Christian Century published a rather remarkable note under the headline, “American Archbishop For Istanbul?” The article reads, in part:

Mystery has surrounded [Maximos’] reported lapses in health, his shuttling back and forth between Greece and Turkey, and almost everything connected with his term in high office. But now it seems that he has stepped out or is on the point of stepping out. And it is reported from Istanbul that his successor will probably be Archbishop Athenagoras of New York!

… There are certain things about the situation in the Near East, however, that we do know. We know that Orthodox leadership there is inextricably mixed up with the political struggle for control of the eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans. We know that the patriarchate at Istanbul is a key post in the struggle. And we know that putting an archbishop from New York in that post is certain to be given a political interpretation throughout that part of the world.

To this knowledge we must add our suspicion that the state department in Washington probably knows more about this proposed choice than any church headquarters in this country. If that should be true — and it would take more than a formal denial to quiet our fears — then it must be said that the United States government is getting involved in a business which will produce plenty of headaches before we extricate ourselves.

Against all odds, Maximos held onto the Patriarchate even longer, for much of 1948. It was a momentous year in Orthodox history for a whole bunch of reasons, including a major pan-Orthodox gathering in July in Moscow to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Russian autocephaly. This was a far cry from the “ecumenical council” that Moscow had originally aspired to host, but it was still a historic event, and it did include a representative from the Ecumenical Patriarchate — Metropolitan Germanos of Thyateira and Great Britain.

Remarkably, Constantinople had sent a representative to Moscow over the objections of its own Ecumenical Patriarch, Maximos. The CIA reported on August 10, “Maximos, Ecumenical Patriarch of the Phanar, was opposed to accepting the invitation of Alexei, Patriarch of Moscow… The Holy Synod of the Phanar, however, overruled Maximos and decided to accept the invitation.” To avoid the complication of obtaining exit visas from the Turkish government, the Holy Synod sent a bishop who was based outside of Turkey. The whole saga of the 1948 Moscow event is a story that requires its own telling. For our purposes here, the striking thing is that while Maximos was Ecumenical Patriarch in name, he seems to have been basically stripped of any real authority.

The very next day, August 11, the CIA issued another report. Strangely, they referred to the 50-year-old Maximos as “aging” and an “old man”:

Protracted maneuvers to replace the aging Maximos as Oecumenical Patriarch of the Greek Orthodox Church appears [sic] finally to be succeeding. For more than a year a large number of the Metropolitans within the Holy Synod has attempted to force Maximos from the Patriarchate… The anti-Maximos Metropolitans have addressed frequent letters to the Greek Government on the subject and have repeatedly called for convocation of the full Synod to compel his resignation. Every time their plans were made to Maximos, however, the old man reacted violently, and twice he had to be dissuaded from actually dissolving the Synod. In the past Maximos has been aided by the Greek Ambassador to Turkey, who on occasion berated the conspirators and advised them to request forgiveness of the Patriarch. It now appears that even the Greek Ambassador no longer hopes to delay the Patriarch’s resignation, and its submission is expected to take place in the next few days.

The most likely victor in the patriarchal elections which will follow within two or three weeks of Maximos’ resignation remains Athenagoras, the Metropolitan of North and South America. The Greek Government has long considered Athenagoras the most desirable successor to Maximos, and within the last week the Turkish Government has indicated that it has no objections to him. Both governments feel that Maximos is incapable of dealing with the recent Soviet efforts to use the Church as a political instrument. With the powerful support of these two governments, Athenagoras is virtually assured of obtaining the Patriarchate. One remaining practical difficulty, however, is the fact that the Patriarch must be a Turkish citizen. Turkey is reluctant to confer citizenship on Athenagoras until the preliminary arrangement[s] for his election are completed.

About the citizenship thing — you might be confused, as I was, about this need in August 1948 for Athenagoras to become a Turkish citizen, considering the earlier report back in July 1947 that Athenagoras had been made an honorary citizen of Ankara. But that 1947 citizenship seems to have been purely “honorary,” and limited to Ankara itself. He still wasn’t a citizen of the Republic of Turkey. (Although he had been a Turkish citizen, originally, before his arrival in the United States. Once he came to America, he gave up his Turkish citizenship and became a naturalized US citizen. At this point, the US did not allow dual citizenship. I don’t know when, exactly, Athenagoras became a Turkish citizen again, although it appears to have happened sometime in late 1948 or early 1949, in conjunction with his election and enthronement as Ecumenical Patriarch.)

Finally, on October 18, 1948, Patriarch Maximos V resigned. On November 1, Athenagoras was formally elected Ecumenical Patriarch.

On November 3, Christian Century wrote of the election,

We do not know what part the United States has played in the high-pressure diplomatic maneuverings which have been going on behind the scenes for more than two years to get Maximos out and a patriarch in who would be more acceptable to Greece and Turkey… [I]f the United States government, in the dim background, has got itself involved in the subtle machinations of Levantine ecclesiastical politics, the day will come when it will rue that entanglement.

The CIA issued a sort of postmortem on the election on November 10, observing that “Soviet attempts to use the Greek Orthodox Church as a medium for persuasion and propaganda have undoubtedly received a setback with the election of Athenagoras.” While Maximos had done his best to oppose Moscow, “he has been so sickly during the last two years as to be sometimes wholly ineffectual… Alexei will probably make new attempts to win friends and influence patriarchs in the Near East, to the accompaniment of Soviet denunciations of Athenagoras (who became a US citizen during his long stay in New York) as a US tool. Nevertheless, the more vigorous Athenagoras can be expected to be far more effective than his ailing predecessor in asserting the leadership of the Ecumenical Patriarchate over the Greek Orthodox world.”

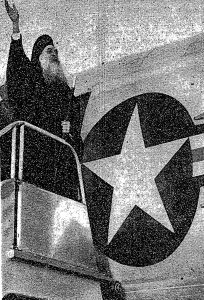

Patriarch-Elect Athenagoras boards President Truman’s plane, “The Sacred Cow,” en route to his enthronement in Istanbul. This photo is from the New York Times, January 24, 1949.

***

On December 1, after Athenagoras’ election but before his arrival and enthronement in Istanbul, the now-former Patriarch Maximos sent a heartbreaking letter to Athenagoras, begging for the new Patriarch-Elect’s compassion, understanding, and help. The letter, published in a 2006 paper by Paul Manolis (begins at p. 258 of this linked PDF), is, in the words of Manolis, “rather pathetic and pitiful.” Maximos dictated the letter to a friend, writing at the end in his own hand that “my nervous condition and overtiredness did not allow me to write while seated.” Maximos tells Athenagoras that he lives “alone, completely alone,” and has been “abandoned” by all. With help from the Greek government, he is traveling to Switzerland for his health. In fact, he remained in Switzerland for the rest of his life.

President Truman and Patriarch-Elect Athenagoras had a meeting on December 16. It is perhaps at this meeting that Truman offered to let Athenagoras fly to Istanbul aboard the Presidential airplane. On January 23, 1949, Athenagoras boarded Truman’s plane, the bizarrely-named “Sacred Cow.” This was clearly intended by Truman to send a political message, as Dr. Alexandros Kyrou explains: “Truman’s extraordinary gesture was not a function of his sentimentality or respect for Athenagoras, both of which, incidentally, were genuine. Instead, this was a measured action taken by a president who viewed Athenagoras and the Patriarchate as influential and crucial partners in the furtherance of US international interests and humanitarian values in the world struggle against communism. Truman’s unprecedented display of presidential goodwill was not intended merely as a personal expression of mutual friendship and regard for Athenagoras, but as a clear indication of Washington’s value of and support for the Patriarchate—a strong diplomatic message Truman sought to send to both Ankara and Moscow.”

Patriarch Athenagoras, 62 years old at his enthronement (and 11 years older than his predecessor Maximos), spent a remarkable 23 years on the throne and was one of the most historically significant (and controversial) figures in modern Orthodoxy. And as Paul Manolis relates, Athenagoras continued to correspond with Maximos, even visiting him in Switzerland and seeking his advice on important matters. While Maximos was certainly a victim of political machinations, he also seems to have been genuinely unwell and not in good enough condition to continue as Patriarch. He died in January 1972, and Athenagoras presided at his funeral.

***

A new day had dawned for the Ecumenical Patriarchate and for world Orthodoxy. With Athenagoras on the throne, the US finally had a reliable, stable leader that could help in the fight against Communism. (Among all sorts of evidence for this, see this 1951 CIA report in which Athenagoras was quoted as assuring the Americans that the Patriarch of Antioch will not “stray from the fold.”)

Patriarch Athenagoras was as complicated a figure as he was significant. He was famous or infamous, in equal measure, for his attempts at rapprochement with the Roman Catholic Church, culminating in his famous meeting with the Pope in 1964 in which they symbolically “lifted the anathemas” against each other. He weathered the brutal storm of the 1955 Istanbul Pogrom (aka the “Events of September”), in which anti-Greek riots led to the mass departure of most of the remaining Greek population in Istanbul. He battled Moscow over the autocephaly of the OCA, arguing that autocephaly cannot be granted unilaterally but must have the consent of all the Orthodox Churches. And he rebooted the process of planning the long-awaited Great and Holy Council, organizing a series of pan-Orthodox conferences that helped thaw relations between the Orthodox countries in the Soviet orbit and those outside of it. For better or worse, he was one of the most historically significant figures in 20th century Orthodoxy.

Biserica Ortodoxă este universală - Blog personal al Părintelui Matei Vulcanescu